Game design is more than just concepts and abstract ideas, although designers are distinct from programmers, they should still have an understanding of games as software. Without that understanding, a designer can’t effectively communicate with their team.

As a technical designer, it’s imperative that I can communicate on equal footing with programmers to ensure design decisions are grounded on what’s technically feasible, rather than providing an unrealistic design that slows down production and builds up technical debt.

Artificial Life Simulacra

Balancing reactivity and technical complexity in game agents is a difficult challenge, but one that can be alleviated by adopting artificial life algorithms, simplifying complex behaviours down to a set of basic rules that guide decision-making. Using open-ended rules as opposed to hardcoded logic has the added benefit of potentially leading to emergent behaviours.

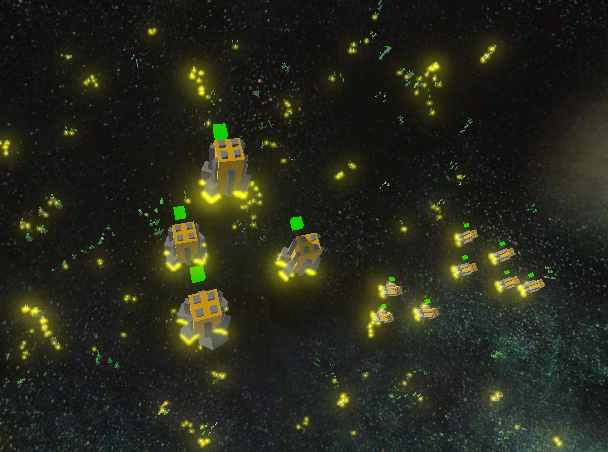

As part of a larger project, I produced a tech demo thematically inspired by the 1988 novel ‘Legend of The Galactic Heroes’, in which agents representing spaceships followed the three basic rules of ‘birdoid’ flocking, the demo also featured a formation system.

The most difficult part of using such algorithms is keeping them within performance budgets, as well as correctly tweaking the weight and rule order to ensure they are appropriate for the agent we’re trying to create. A-life is not always the correct solution, but it is an often overlooked one.

The demo was made using Unity’s Entity Component System complemented by a linear octree (for faster memory access), enabling for 10000 agents in-engine to flock around. With further optimizations such as staggering updates, this could be pushed to 50000.

Advanced Pathfinding Solutions

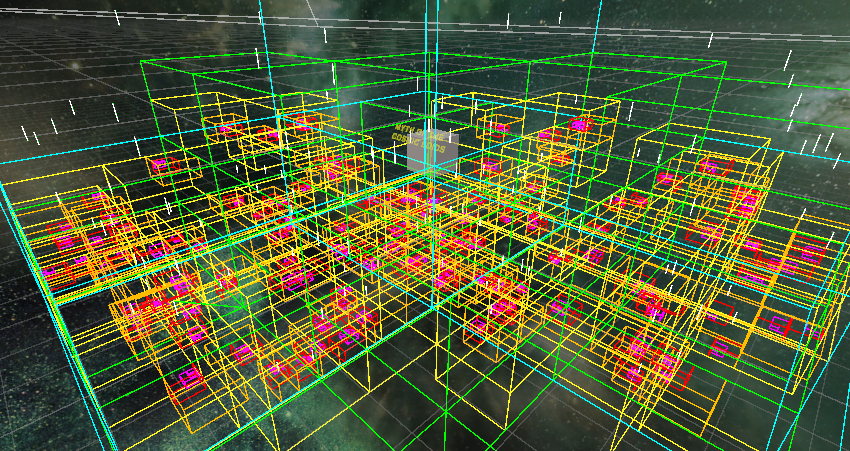

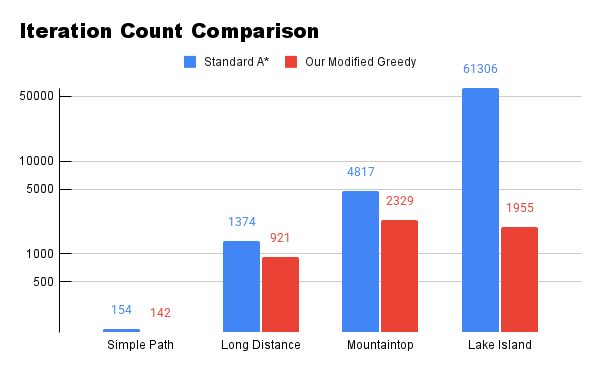

Like most technical minutiae, designers don’t often think about pathfinding, believing it to be a ‘solved issue’ and proceeding with textbook implementation before moving onto more ’exciting’ parts of the game design process. However, a textbook implementation isn’t always a good fit for a game. Some games may require highly optimized algorithms for simultaneous use by many agents or for long distance traversal, while others with a larger performance budget may be able to afford purposefully suboptimal pathfinding for aesthetic reasons.

Regardless, the responsibility of finding the right algorithm for the job falls upon the technical designer.

There was a project in which we managed to greatly reduce iteration counts by adopting a modified greedy algorithm (that still weighted for water and terrain hazards), we then combined this with a hierarchical pathfinding system that enabled 50 kilometres to be pathed through in the same amount of time that two used to take. Later in that project, we used a system to adaptively switch algorithms based on the environmental context of the agent, with more standard A* used when nearing the player, and a special flowfield-based pathfinder when navigating dense urban environments.

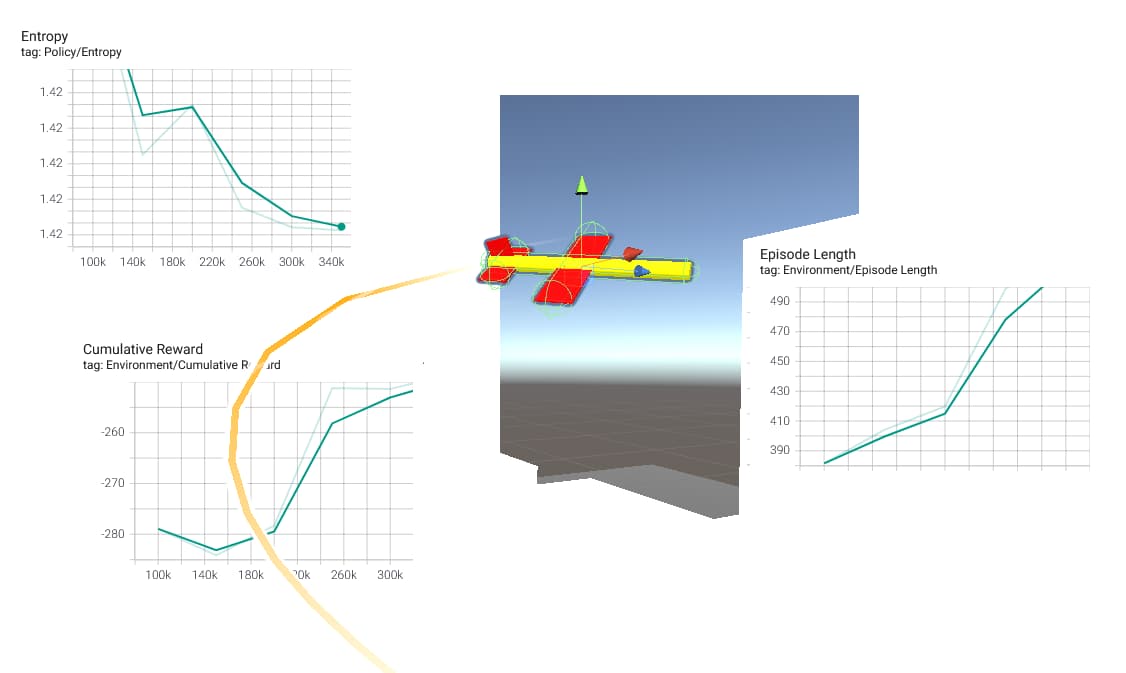

Real Time Speech Synthesis & Machine Learning

After experiencing the fun of roleplay servers in Vintage Story, I embarked on a project to implement speech synthesis into the game as an inclusivity tool, providing natural-sounding voices in real-time to players that lacked a microphone or were too shy to speak, preventing them from feeling excluded in servers where using a microphone was often the expected method of communication.

While other games have utilized speech synthesis as a cost saving measure to replace voice acting labour, my objective was to have a runtime implementation capable of handling novel on-demand requests. The result of my research was an implementation with a memory footprint of just 25 megabytes per speaker, lightweight enough to run on any consumer computer processor without GPU acceleration of any kind.

The implementation incorporates Xiaomi Corporation’s open neural network exchange (ONNX) (maintained by Fangjun Kuang) alongside Stellon Labs’s state-of-the-art (SOTA) text-to-speech voice synthesis model, natively running in-game.

To my knowledge, this is the world’s first and only real-time machine-learning-based local speech synthesis implementation in a game.

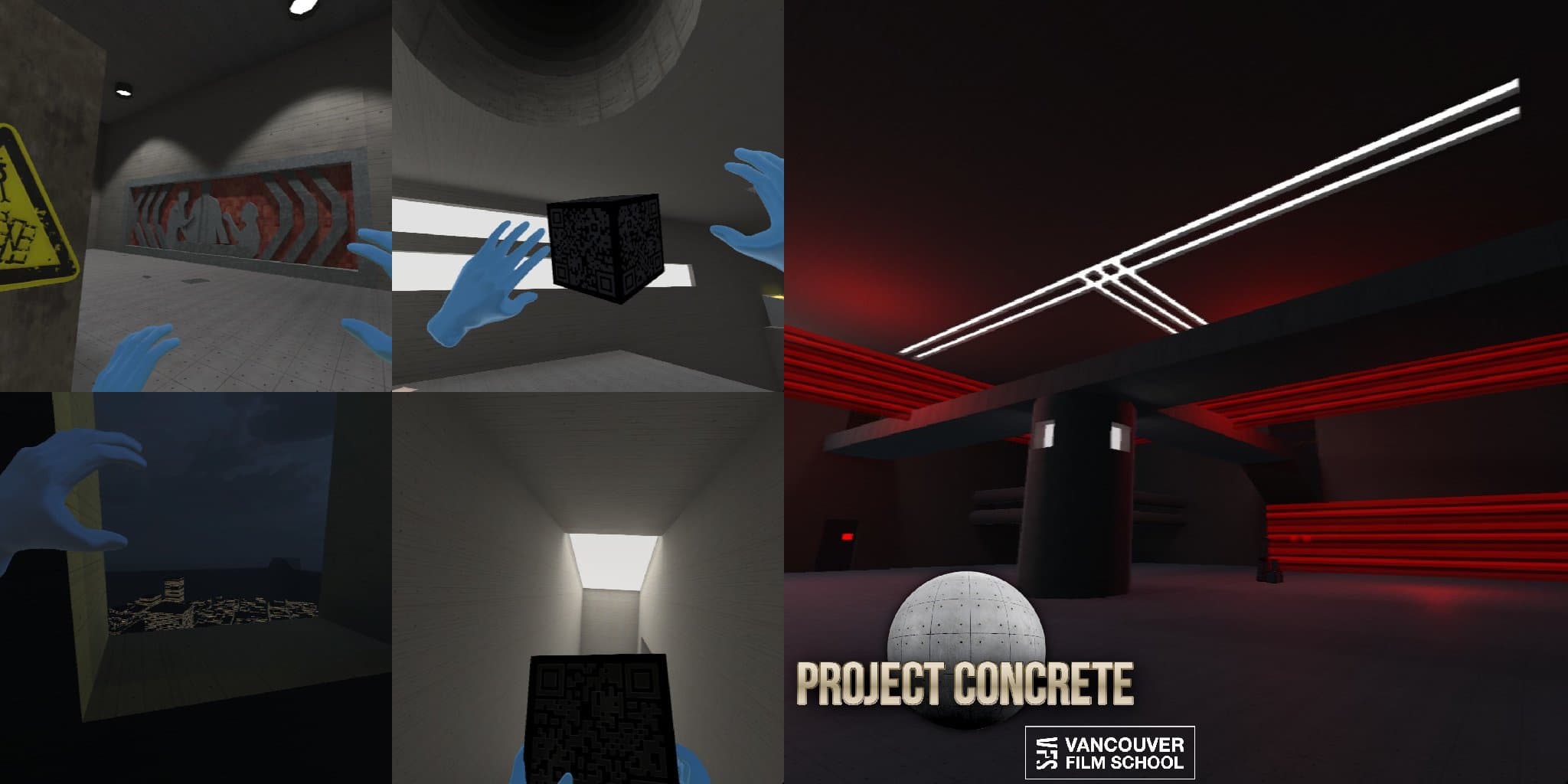

As a footnote, half a decade prior to this, my graduation project at Vancouver Film School used Microsoft’s Eva model for speech recognition, allowing players in a VR environment to activate special powers with voice commands (à la wizard’s incantation style). I’ve been pushing the envelope on the usage of machine learning in games for the purpose of accessibility since well before the current AI craze.

Pipeline Improvement

As corny as it sounds, it’s not enough for a designer to answer questions, they must also be able to question the answers –to challenge established standards and evaluate if they’re still relevant in our ever-evolving industry. The games industry moves fast, the cutting edge quickly becomes dull, and workflows established early in a company’s lifecyle often fail to scale as they grow. Designers are the only ones with the multidisciplinary understanding of everyone else’s work necessary to help to orchestrate production-wide workflows changes, acting as mediators between departments as they each weight the requirements and needs for transitioning into a new pipeline.

Here’s a list of pipeline improvements I’ve partaken in throughout the years:

- Led an initiative to transition outdated and unreliable cloud-hosted documentation into an internally hosted company wiki

- Implemented an advanced machine-learning OCR tool to transcribe physical documentation into a digital format

- Argued for the employment of procedural techniques to modernize artists’ workflows, would later be in charge of R&D for a similar initiative

- Developed in-house snippets, tools, and plugins to improve programming and content authoring workflows

- Was on multiple occasions included in panels to discuss technological and engine changes

I’m passionate about optimizing and improving workflows not only to make the most out of the resources at hand, but also to ease the workload on my co-workers. I’ll always strive to find ways to continue improving pipelines and workflows.

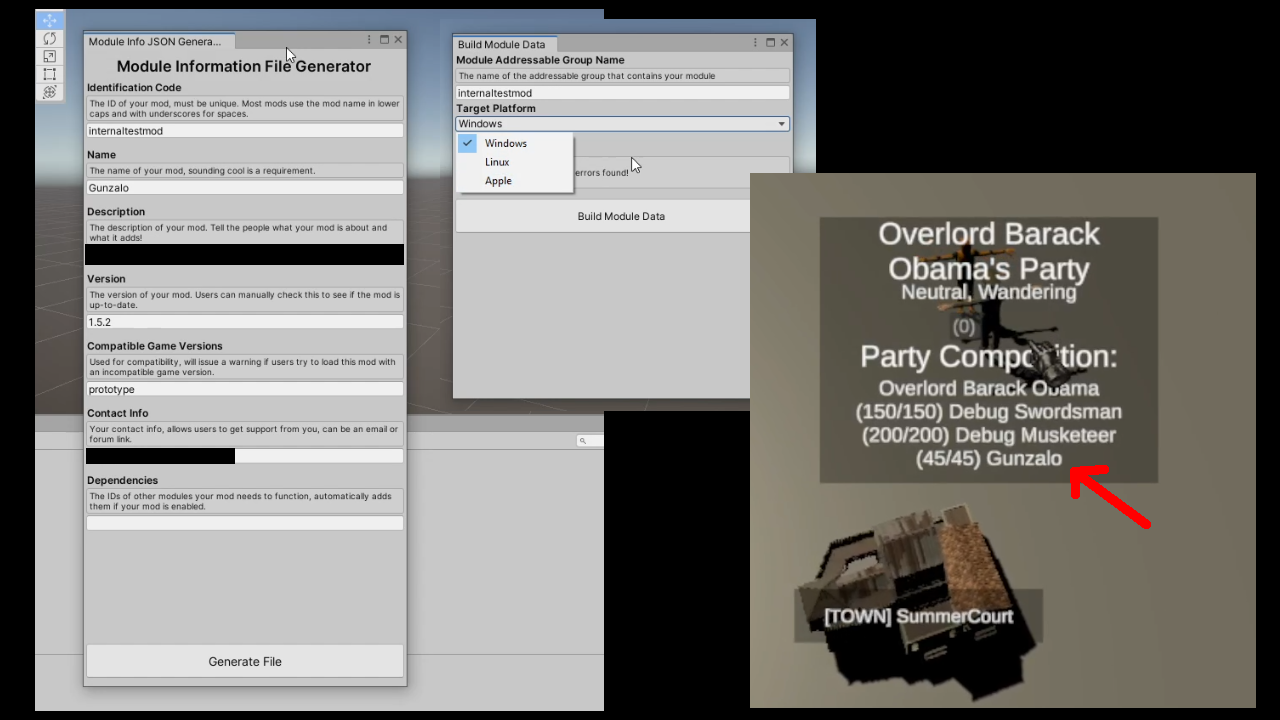

Transcodification & Game Modifiability

Every operation in a game is either performed on in-memory values, or involves processing data out of disk and into memory. For this reason, I’ve had to design my fair share of file format specifications for games where plain JSON or XML wasn’t enough. From new subtitle standards, to little endian binary data formats, to entire modding structures.

The project in this field I’m proudest of was a real-time strategy roleplaying game where I was in charge of the entire modding system, designing and implementing a system to parse structured files into internal data structures, and external tools to quickly author them.

Although the project itself never bore fruit, the modding system I designed for it was still the best work I’ve done to date.

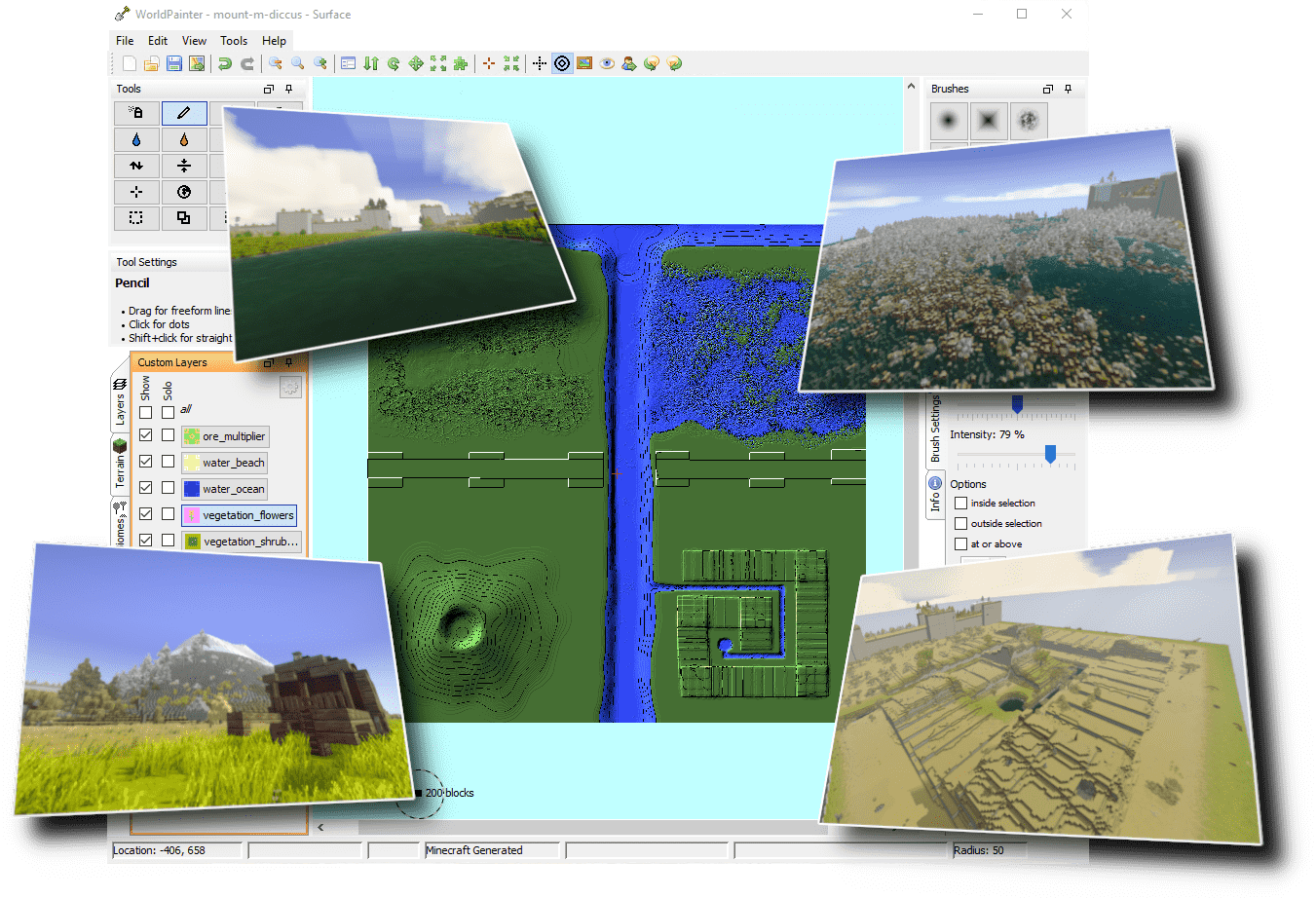

Another thing I worked on was World Painter for Vintage Story, a project to compatibilize a third-party map authoring tool with the game Vintage Story. For this project, I settled on using a little endian binary format to store raw heightmap and layer data, allowing for fast data access. Inside the game, the data was fed into the game’s terrain generation systems via reflection.

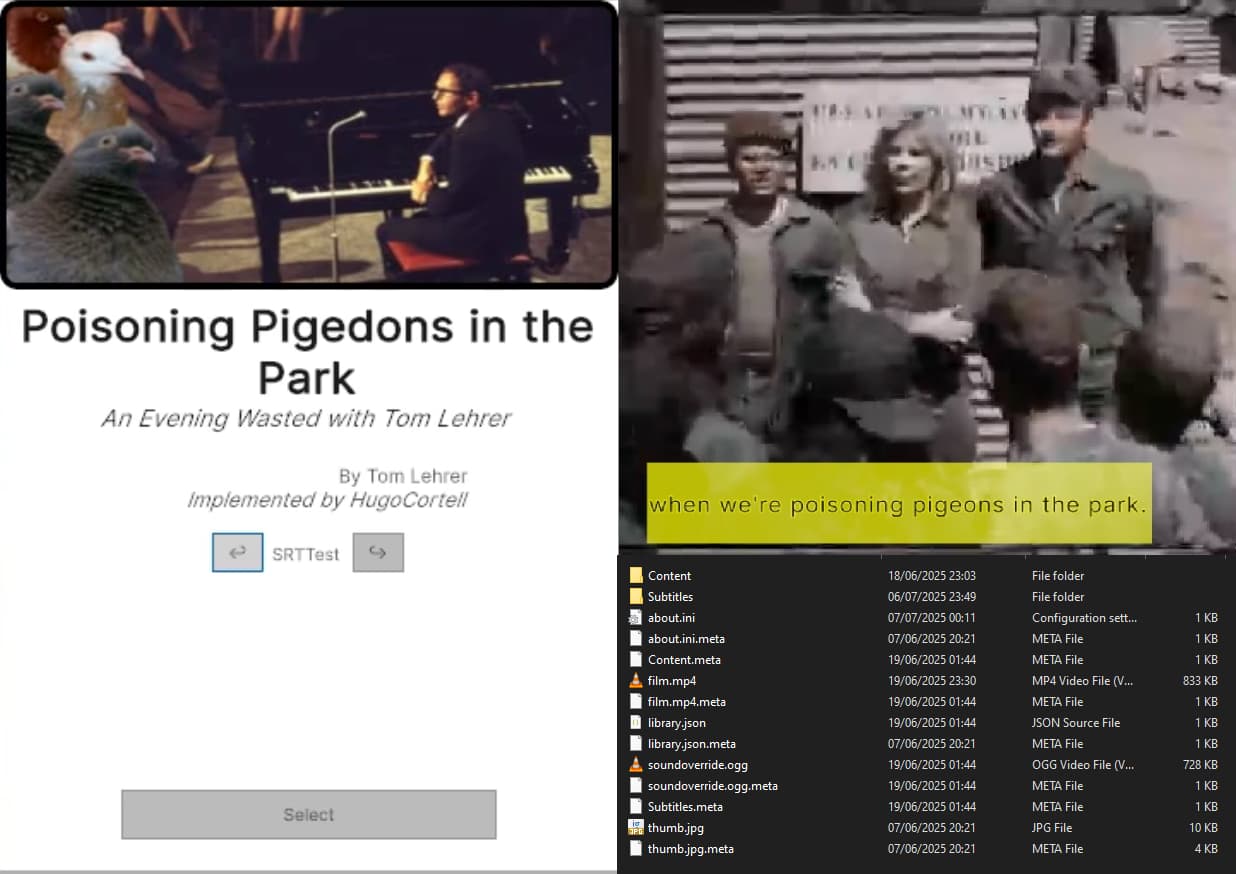

Another project I worked on was an open source karaoke & rhythm game, the game was designed from the start with a core focus on making user-created content as easy as possible, featuring support for multiple subtitle formats alongside my own human-readable format designed for ease of use while providing powerful features like keyframe animation, colour changes, and other features.

Ultimately, the goal was to support slideshows, videos, online streaming (for legally accessing otherwise unlicenced content), and real-time 3D animations for a karaoke (and rhythm game) software that was as artistically varied as it was flexible in its subtitle features.

Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality

I was an early and eager adopter of Oculus-era virtual reality technology, believing in the promise held by the inherent immersion of virtual reality. In those early days, designers were excited to solve the novel challenges of the platform, such as movement, interfacing (UI), level design (in particular leading attention), and dealing with motion sickness.

During this period in which design best practices still hadn’t been established and many large studios were struggling to make the most out of the medium, I worked on my graduation project at Vancouver Film School: a VR game that was a pioneer of many things. Featuring a purely diegetic user interface, slide movement (back when people thought teleportation movement was the only way to avoid motion sickness), and a voice recognition machine learning model that allowed the player to trigger special actions and navigate dialogue trees without complicated controller mappings.

The virtual reality game market never grew to be significant, but there’s potential for smaller games to carve out a profitable niche in. I spent years developing early VR games, so much so that the weight of early HDMs during debugging sessions notched my nose. Now, I can undeniably claim that I’ve got a nose for technology.